Have you ever shuffled through your living room carpet in socks and touched a doorknob to be met with a pop! and a shock? That’s what’s happening in the clouds during a thunderstorm.

Our eyes deceive us when lightning strikes like a giant spark cracking the sky in two. That giant spark is only as big around as a golf ball. Like everything else in nature, it happens for a reason. The Earth and the atmosphere both carry an electrical charge, and strike by strike, lightning equalizes the difference.

What is lightning, anyway?

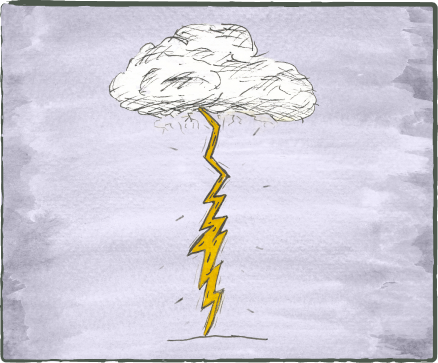

The drama happens in the cloud’s center, cooler than the inside of your kitchen freezer, when ice crystals and soft hail called graupel collide and transfer electrical charge. Positively charged lighter ice crystals loft to the top of the cloud while negatively charged heavier graupel fall lower within it. Another positive layer at the cloud’s underside sandwiches the negative graupel. The thundercloud’s life, usually half an hour, restores the equilibrium by connecting with the ground, which has a different charge.

One flash takes three steps, over in a second: The step leader, the ground streamer and the return stroke.

- Step leader:

Think of your first time at a house party: full of nervous energy, desperate for some connection with anyone or anything. The step leader rushes toward the surface in an attempt to make contact. It begins in the cloud and moves in surges toward the ground, too faint to see. After 150 feet, it finally happens.

- Ground streamer:

As the step leader rushes down, another charge from the ground now rises to meet it. That welcoming charge is called the ground streamer. Once the step leader is about 125 feet away, the ground streamer reaches up to meet it mid-air, establishing a bond. That’s called the conducting path.

- Return stroke:

A relationship forms. The stress-energy dissipates. The vibe becomes stable. Yet one stroke isn’t enough to sufficiently de-charge the cloud. It takes several strokes forming bonds for the negative charge to drain. The bonds are the part of lightning we can see. On a high-speed camera at 20,000 frames per second, sparks like fireworks explode all around the step ladder and return stroke. Then the party ends. Until next time.

In the time it takes to read this sentence, those steps have happened about 300 times around the world.

What triggers lightning?

Lightning takes a thunderstorm. Thunderstorms require moisture, instability and lift.

- Moisture is the fuel for thunderstorms. Sea breezes and wind carry moisture from other water sources.

- Instability means air of different temperatures in close proximity. Warm air rises like a hot air balloon while cool air lags below.

- Lift can mean wind, but it can also come from the movement of sun-heated air, the meeting of cool and warm air at fronts and even cool air left over from an earlier thunderstorm.

Florida is the perfect landscape for this trifecta as a peninsula with the Atlantic on one side and the Gulf on the other. Year-round sunshine and the sea breeze also help make it the lightning capital of the United States with more strikes per square kilometers than any other state.

Lightning strikes about two billion times annually; one in 10 of those strikes is in the United States. Chris Vagasky, a researcher for the National Lightning Safety Council, said the number of strikes hasn’t changed much in his decade studying lightning, but the locations of strikes have shifted.

Florida sees more than 15 million lightning strikes a year, according to the National Lightning Detection Network.

Test Your Lightning Knowledge

Myths vs. Facts

Test Your Knowledge of Lightning

Myths vs. Facts

A tree can shelter you

from lightning

Test Your Knowledge of Lightning

Myths vs. Facts

A tree cannot shelter you

from lightning

Under a tree is among the most dangerous places to be during a thunderstorm. Doing so is the second-leading cause of lightning deaths.

Test Your Knowledge of Lightning

Myths vs. Facts

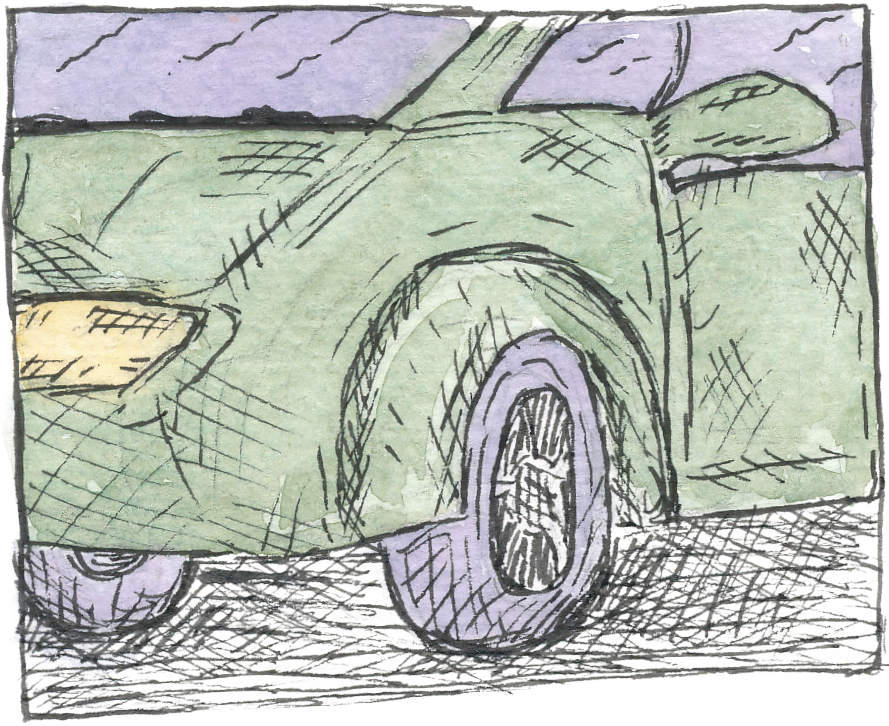

A car’s rubber tires on asphalt will protect you from lightning

Test Your Knowledge of Lightning

Myths vs. Facts

A car’s rubber tires do not protect you from lightning

If you can’t get inside, a car is your next safest spot. But it’s the car’s frame, not the tires, that does the most to keep you safe. Lightning pulses through the metal frame and then down the tires to the wet asphalt, diverting the strike from you.

Test Your Knowledge of Lightning

Myths vs. Facts

Lightning always strikes the

tallest thing

Test Your Knowledge of Lightning

Myths vs. Facts

Lightning does not always strike the

tallest thing

Objects that are tall, isolated and pointy are the most attractive to lightning. But just because something is more prone to be struck doesn’t mean it will be.

Test Your Knowledge of Lightning

Myths vs. Facts

If you’re not directly under the lightning cloud, you’re safe

Test Your Knowledge of Lightning

Myths vs. Facts

If you’re not directly under the lightning cloud, you are not necessarily safe

Lightning can extend six miles from the edge of the cloud that produces it.

How strong is lightning?

Lightning is measured in Kiloamperes (kA). An ampere (amp) is the unit used to measure the flow of electricity, and a kiloamp is a thousand amps. Think about the power outlet you plug your computer into. That’s about 15 amps of current. The average stroke of lightning is 20 million to 25 million amps

Lightning only lasts for a millionth of a second. So a strike to a person takes fractions of a second; it’s not a direct continuous flow (like if you were to stick a fork in an outlet). But because the amps are so high, the risk of injury or death is much higher.

Most people aren’t directly struck by lightning. Vagasky said when most people hear someone was struck, they think it was through the head. But that’s just one of five ways, and not the most common. More frequently, lightning strikes ground nearby, and it goes into the person briefly before the electricity dissipates.

Ninety percent of people struck by lightning survive. If their feet are close together when they’re struck, they’re even more protected. That’s one of the reasons animals tend to be injured more frequently than humans; their legs are further apart, leaving them with greater potential for energy transfer. Also, when electricity goes from the ground up their legs and across their body to go out the hoof of the next leg, it crosses all the animal’s vital organs.

What is thunder?

A lightning strike heats surrounding air to 50,000 degrees Fahrenheit, five times hotter than the surface of the sun. Such extreme, rapid-fire heat creates a shock wave: Thunder. Because the speed of light travels faster than the speed of sound, you see lightning’s flash before you hear thunder’s roar.

Thunder can help you estimate lightning’s distance. Once you see a strike, start counting until you hear thunder. Every five seconds roughly measure one mile. Thunder can reverberate for 15 miles, so it could be up to 75 seconds before you hear it.

What’s my risk?

As a Floridian, you’re more than 500 times more likely to be struck by lightning than win the Powerball jackpot in a given year.

Any time you’re outside during a thunderstorm, you’re at potential risk.

When clouds are taller and look like cauliflower, that’s the beginning of a thunderstorm. When those clouds flatten out and look like an anvil, that thunderstorm is mature and ready to strike. When the sky darkens, the wind picks up, you hear thunder or you see lightning, take it as a cue to get to a safe place.

While the science of detecting lightning has improved greatly since formal research began in the 20th century, Henry Fuelberg, a leading lightning researcher at Florida State University, said it’ll be a long time, if ever, until scientists are able to predict the exact location of a strike.

According to Harvard researchers, lightning may have provided the chemical elements that helped create life on Earth. It continues to dazzle scientists and awe humanity today. As the climate becomes increasingly unstable and heat ramps up, only time will tell what the future holds for lightning.